Guest Post by Nicholas Delbanco

Robert Frost Distinguished University Professor Emeritus of English, University of Michigan

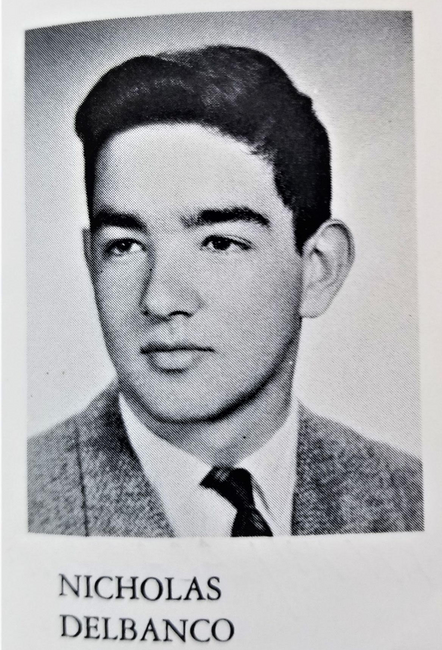

First, a personal note. I have known the DADvocacy Consulting Group's and Daddying blog’s founder Allan Shedlin since we both were children, most of a lifetime ago. We sat next to each other in the classrooms of our secondary school (photo below is from our 1959 senior yearbook); we went to different colleges but kept in touch. I knew his parents, he knew mine. Later, I knew his children and he mine. Our two daughters (one on the West Coast, one on the East) remember him from childhood, and now they have, collectively, five children of their own.

So, this is scarcely an objective essay; it’s full of the kind of subjectivity that a history of friendship brings to bear upon a topic, and intentionally so. I’m grateful to my enduring friend for the permission he gave his old friend to muse in public about private things. No attempt here to offer up general truths but only some specifics about one man’s experience of fathering and grandfathering. What follows is a very small entry into a very large account book of profit and generational indebtedness.

Some years ago, at her younger sister’s first birthday party, the then six-year-old Penelope offered to make and put up a sign instructing the assembled guests how to dispose of their trash. It was a garden party – paper plates and cups, ice cream, cupcakes, and the paraphernalia of celebration: hats, balloons, bottles of juice, and hot dogs on the grill. There were two garbage cans. Penny has an artistic nature; she lettered carefully, colorfully, then scotch-taped a sheet to the cans. This is what she wrote:

CEEP THE

RTH CLYN

RYYOUS

RYDOOS

RYSIYCL

Her school is a progressive one, earnest in its desire to instruct its students how to salvage or at least preserve the planet. What she was writing, for those readers who might require translation, was: “Keep the Earth Clean. Re-use. Reduce. Recycle.” When, however, I offered to help the six-year-old with spelling, she shook her curly head.

“No, grandpa,” she said. “I prefer best guess.”

Best guess. Those of us who have no faith in spirit-life beyond bodily life can nonetheless believe we may be remembered, and fondly, by those who carry on. One of the ways a grandparent can dream of immortality has to do with the survival of future generations; it’s how we tell ourselves an afterlife exists. The family album or old tale told or anecdote recounted or shadow-face in the mirror is in this sense a marker of immortality: tricked time. When offering to help a six-year-old with spelling, I have the shadow-sense of being helped, myself, at six…

Best guess. I thought long and hard about marriage – what it would mean in general terms and which specific woman I would ask to be my wife. Once married, I thought with some degree of focus on what it would entail to become and be a father. But I gave scarcely any thought to the matter of being or becoming a grandfather. That was, or so I told myself, something old people dealt with and not a pressing concern. It was in the cards, perhaps, but not in the hand I was playing. Too, when I remembered my grandparents – three of whom had been alive for much of my own childhood – it was from a respectful distance. They had been present absences to whom I was polite. Our interactions were formal, in part perhaps because of the “old world” nature of their expectations and their own nineteenth-century childhoods, in part because they seemed to me like creatures from another planet: plump, heavily accented, smoking cigars, drinking schnapps.

So, now that I’m a grandfather (five times over, with five granddaughters), I ask myself if those young girls consider me also a stranger – not in terms of name or face recognition but in terms of the way I behave. I don’t understand the rules of their games or the lyrics of the songs they sing; I’m incompetent at the technologies with which they’re already at ease. I feel much closer to my grandparents now than was the case when they were alive, and the bemused inattention with which these young girls tolerate my eccentricities feels all too familiar. They run where I walk; they dance with agile abandon while I twirl in slow stately measure on the kitchen floor.

Once married, I thought with some degree of focus on what it would entail to become and be a father. But I gave scarcely any thought to the matter of being or becoming a grandfather.

Frederica, now eight, delights in “teaching” me ballet; she goes to dance class and comes back determined to demonstrate the details of an arabesque or jeté. I huff and puff and raise my arms above my head and bend and glide, or try to, as she instructs me, and my evidenced incompetence elicits gales of laughter. It pleases me, of course, to be the buffoon-like butt of the joke, but sometimes I remember what it felt like years ago to watch my parents and grandparents dance on those few formal occasions they did so, and a sidelong glance in the mirror reveals my father’s face.

He died at 98. Two years before his actual demise he took a fall and was hospitalized. Fearing this would be our farewell visit, I flew east. When I entered the hospital room, he raised his white head and opened his eyes, and said to me, “I am not dying yet. But I am more ready for death than for life.”

Those sentences have stayed with me. I wonder at what moment and in how near or distant a future I will say the same. A principle delight, these years, is quite precisely the one I did not plan for or envision: being an old person who watches his children’s children through the years. This is a commonplace feeling – almost everyone I know responds in the same way to our newfound circumstance – but it does not diminish the joy. To have grandchildren and to see them grow is, purely and simply, a gift.

Nicholas Delbanco is the Robert Frost Distinguished University Professor of English Language and Literature, Director of the MFA and Hopwood Awards Programs at the University of Michigan. He is the author of 31 books of fiction and non-fiction, including The Count of Concord and Spring and Fall (fiction) and The Lost Suitcase: Reflections on the Literary Life, Lastingness: The Art of Old Age, and The Art of Youth: Crane, Carrington, Gershwin, and the Nature of First Acts (non-fiction). As an editor, he has compiled the work of, among others, John Gardner and Bernard Malamud. He also has written and co-edited with Alan Cheuse a teaching text for McGraw-Hill titled Literature: Craft and Voice, a three-volume Introduction to Literature. Professor Delbanco has served as Chair of the Fiction Panel for the National Book Awards, received a Guggenheim Fellowship, and, twice, a National Endowment for the Arts Writing Fellowship. His most recent work of fiction is the novel It is Enough, his most recent work of non-fiction is Why Writing Matters. Next year, his collected short stories Reprise, and Other Stories will appear.

Comments